|

At our expedition’s end we left Kangirsuk with very little waste. Much of the waste we generated came from traveling—packaging from food we purchased on our travels to and from Umiujaq and Kangirsuk. A summary of our expedition waste:

Items that were recycled:

Our trash bag was tiny! The area we traveled through had very little impact from modern day travelers and we picked up little trash along the way. In working to execute a zero waste expedition we learned that it was relatively easy for us to make conscious decisions about small things; how to pack our food, waterproof our gear, and bringing reusable bags to the grocery store when we purchased food. Much of the waste we accumulated came from product and food packaging. Every bulk food item or piece of gear we mail-ordered prior to the trip seemed to come packaged in an excessive amount of plastic or new cardboard. In the small Northern towns in Nunavik every vegetable was packaged in plastic and Styrofoam. It was hard to watch Air Inuit cargo workers shrink wrap our cargo with a large amount of single use plastic. However, after contacting Air Inuit about this, they did say they are looking for alternative ways to organize their cargo. We can't completely avoid single use plastic, though we can be active conscientious consumers. When you find a company that doesn't ship items in plastic, thank them. When you're frustrated with your options speak up! How did we minimize waste?

We made 200 reusable waterproof food bags prior to the expedition. All of our dry foods were packed in these bags. Our food bags were then packed into barrels lined with Ostrom pack liners. All of our food was packed by meal, meaning we planned specific meals over the 45 days. Our meals were organized in 4 sections each including about 12 days. In each section instead of eating 12 different things for breakfast, lunch, or dinner, we planned 4 different meals and ate them three times each. This allowed us to use less bags because we could pack more than one meal in a bag. Our barrels were watertight, the Ostrom pack liners were fantastic, and all of our food stayed fresh and dry. The food bags were durable. Over the course of the trip none of our bags broke or ripped. A few of the bags we used daily to pack individual rations of snacks, to carry handmade bread for lunch, to grow sprouts, and even sew a new crotch in Steve's rain pants. After the bags were emptied they were packed back into a barrel where they stayed for the remainder of the expedition. At the expedition's end I flipped all the bags inside out, rinsed off the powders in the sink, and put them all in the washing machine. Almost all of the bags came out looking link new. We did discover one food item that created some staining—pumpkin seeds! As of now the bags have been put away are awaiting their next adventure. What's next? I plan to continue working on developing this idea. Long term I hope to create a product that can replace single use plastic bags for food packing in the outdoor programming industry. Short term I plan to continue to evolve the design and field test the bags in a variety of conditions and environments. Apeiron Expeditions is field testing bags in Maine. Contact me if you are interested in trying them on one of your own adventures.

2 Comments

At the heart of our travels these last two months are two words: adventure and expedition. To go adventuring—to explore the unknown, to embrace uncertainty, to exercise curiosity, to take advantage of opportunity. Expedition—a means of which to seek out adventure, to travel self-sufficiently, to co-exist with the land, to accept, with grace, all that might arrive. Choosing adventure by expedition challenges our core beings and in the end we leave with wiser eyes. Returning from expedition presents its own set of challenges. On the morning of day 46, August 19th, 2018 when we landed on the beach in Kangirsuk, Nunavik, Quebec, you could see it in our eyes. Smiles, tiredness, relief, excitement, hunger, bittersweet. We had sun and wind-burnt faces, bags under our eyes, unkept beards, mustaches growing past upper lips, and worn hands. Upon closer inspection one could see layers of dirt caked on once brightly colored dry suits, matted hair hidden under layers of hats, patches on boats, dead mosquitos and black flies caked in every nook and cranny, and fresh baked potato flake and flour biscuits in our bowls. We made it! Our feet finally planted on the low tide beach in the Inuit community of Kangirsuk! In that moment, if you asked, "How was it?" your question likely would have been met with a blank stare, or wide eyes and a smile. "How was it?" is not an easily answered question at an expedition’s end. An expedition, especially an adventurous one is often everything. We were on expedition for 46 days; that's 1,104 hours. We slept around 315 hours. That leaves 789 hours of adventure to lakes, rivers, oceans, rocks, musk ox, black bears, mud, moss, fish, rain, rainbows, sun, wind, waves, sunsets, sunrises, full moons, rapids, tides, geese, eagles, ducks, caribou, willow, dwarf birch, and cranberries. To Inuit culture past and present and the kindness of the people of the north, we experienced a world class adventure, a true expedition in every sense of the word. We arrived in Umiujaq on July 3rd. We spent the following two days organizing our gear at the Tursujuq National Park office. On the afternoon of the second day after a large thunderstorm, the ice on Hudson Bay cleared enough and the water was calm enough to begin our adventure and we set fourth, north on the bay. The following two days we spent weaving through icebergs. It was quite magical. They were white, blue, and beautiful. On the bay we saw lots of musk ox, black bear, and took a short excursion to Nastapoka Falls. The Richard River lies 4km north of the falls and marked the end of our journey on the bay. The Richard greeted us with cold, misty wind. We woke up at 3am to big winds, rain, and lightning. Looking east we could see the Richard climbing the mountains, its flooded waters pouring over waterfalls sending spring ice melt into the bay. Our journey east began on foot, cold and wet. The following 5 days we spent mostly portaging with some lining and paddling. Each portage, each of us took three trips. We carried 4 food barrels, 1 food bag, 1 gear bag, 4 personal bags, and 2 boats. Our backs hurt, our legs tired, and we watched Hudson Bay disappear as we climbed higher. We collapsed atop ridges at the end of several days, too tired to keep portaging. Once we neared the top of the watershed, we were able to paddle more, sneaking through the winding river beneath the mountain peaks that continuously gave us the illusion that we were going to paddle off the edge of the world. The grassy, mossy landscape of the coast gave way to rock and snow patches. We finally portaged over the height of land up and over a mountain, into a series of lakes and ponds that led us to Lac Minto. We arrived to Lac Minto on day 12. The prevailing westerlies stayed strong and we sailed our way eastward, stopping to inspect caribou antlers and sleep in tiny protected coves. One morning we woke up to misty rain and within a few hours the weather became warm and sunny and the water flat and glassy. It stayed that way for two weeks! On Lac Minto we caught our first fish, three lake trout weighing in at 8 lbs. Lac Minto soon gave way to the Leaf River. The warm weather brought bugs, black flies and mosquitoes. The Leaf was swollen with spring run-off and provided us with invigorating big water paddling. These big water class III/IV rapids tested our skills and gave us much excitement, and a ferry that would have earned us bragging rights—if anyone was around to see it. We left the Leaf and began our second up river adventure on the Vizien on day 18. The Vizien marked the point where we stopped our eastward progress and headed up river north and northwest for about 58km. The Vizien was beautiful—amazing rapids and blue green crystal clear water. The hydraulics on the river were emerald green in the bright sun. The brook trout fishing was unmatched. Here were perfected our lunch fishing, filleting, and fish carrying techniques. We lined, lined, and lined, and portaged, and paddled up river. After the Vizien we entered the land of lakes, rivers, rock gardens, and subarctic barren lands. At times it was questionable if we were on a lake or a river (hard to imagine), and we found ourselves paddling or lining through many shallow rock gardens. We crossed the height of land through a beautiful 2 km portage on day 29. We entered the water of Lac Bisson, marking our entrance into the Payne River watershed. We spent the next days linking together small lakes and streams (downriver) that brought us to Lac Tassialouc. We stopped mid-day on Lac Tassialouc to fillet some big beautiful arctic char, later realizing 18 lbs. of live fish meant fish for dinner and lunch. Lac Tassialouc gave way to the Tassialouc River. The river was perhaps some of the best and most exciting days of paddling. The whitewater was incredible, really fun, technical class III rapids. We had no prior knowledge of the river and every bend was a surprise. The flat and barren landscape began to transform into rolling hills as the river fed us into Lac Payne. After many days traveling north we finally began heading west toward Ungava Bay. The westerlies and big fetch carried us quickly east. We did stop to explore ruins of past settlements—tent circles, pit houses, and food caches dotted the shore lines of Baie Aarialakallak, where the Payne River leaves the lake. The Riviere Payne began with fury, a long treacherous class V rapid. The portage was made easier by our well-developed caribou trail tracking skills, their trails always leading us through the path of least resistance, through thick willows, dwarf birch, around rock piles and marshes. This portage, our last portage, also highlighted our ability to navigate these trails half blind, with sunglasses on, bug shirt zippers closed over faces, sweaty sunscreen dripping in our eyes, a thick cloud of black flies swarming, and boats on our heads. That evening we camped in a beautiful place on a plateau above the rapids in the biggest clouds of black flies I could imagine. We're still pulling black flies out of corners from night 37. As we continued down the Payne we found big rolling green mountains. Spring ice melt was long gone and the flow, normal. The rapids were easy to navigate and fun. The kilometers melted away. We soon entered a magical caribou land. Caribou lined the shores and swam across the river heading south. Here we stopped for a day, on day 42, our first break from expedition travel in over a month. The following days the caribou lessened, the rapids grew less frequent, and the river widened. Cabins appeared on the shore line. These hunting and fishing camps signaled that we were nearing the end of our journey. 61 km west of Kangirsuk, we paddled our last rapid and watched in awe as it changed with the rising tide. The tidal difference in the river was enormous; bigger than anything any of us had ever experienced. As we continued east the river's shores were lined with rocky cliffs and rocky shoals that extended far into the river at low tide. Big winds and following seas created big waves and sent us into the shoals with our tails between our legs, letting us know that Kangirsuk would not come so easily. We took refuge in an exquisite flat spot high above the high tide line nestled in the cliff. One more long day of paddling brought us in sight of Kangirsuk. On night 45 I fell asleep to town lights 13km east. In the morning as we paddled flat, glassy water and looked down toward Ungava Bay it was hard to imagine that our journey was coming to an end. We traveled 931 km by foot and canoe linking together two big watersheds with a seldom traveled route where animals looked at us with curiosity instead of fear. So, how was it? Indescribable. It was everything. Incredible, at times horrible, fun, wonderful, hard, cold, warm, really cold, hot. We were tired, hungry, full, rested, sore, strong, weak, joyful, sad, and excited. We moved fast, we were slow, we broke things, we fixed things. We caught fish, we missed fish, we ate fish. Sometimes we wanted the trip to end and sometimes we felt like we could paddle and portage forever. It was everything. Everything and far beyond. None of us would trade this experience for the world.

We meet our goals and finished the expedition with very little waste. Our food bags and food packing system worked fantastically! Our bags proved to be more durable than plastic and none of our food spoiled. Our waxed Cabot Cheddar was excellent, still tasted great and was almost completely mold free on day 42. Thanks Cabot! Stayed tuned for an update on implementing a single use plastic free expedition. In upcoming posts we will do our best to give you insights into our experiences. Let these spark your curiosity to ask us questions. Like CanoeUngava on Facebook. A link to more photos coming soon! -Beth Jackson  WOW! The last month has been a whirlwind on steroids. I returned home from Brazil, spent about 8 days at home cleaning gear and visiting family; I also packed for the summer. Next I drove to Vermont for our trip planing weekend, followed by a month long stint with Hurricane Island Outward Bound, I taught some staff trainings, attended other trainings, jumped in a few rivers, played in my boat, and spent almost all my free time on trip prep. There was a four day period in which I placed 4 Amazon orders. It's sometimes hard to remember everything at once. After I finished work, I had 10 days to make trip planning my full time existence. First I sewed then second I packed. Simple right? Let me enlighten you. Food Bag Production 200 pennies isn't a lot when you count them. 200 M&M's could accidentally be eaten over the course of a day, Holy moly 200 food bags is A LOT of sewing. I thought two people could sew food bags easily in two days. My friend Meganne volunteered to help. Meganne spent 4 hours on her knees expertly cutting 27 yards of fabric into 200 individual pieces- and they were square! I sewed. The next day, I spent 7 hours trouble shooting sewing machines, meanwhile Meganne sewed like a machine! The following day I sewed on all the ties and finished all the bags. Eli's mom, Joanna helped us out by making 40 bags. After three days of food bag production, my butt hurt from sitting, I put a huge dent in my tea collection and ate way to much take out. I dreamed about food bags, more than once. Food Pack The morning after the food bags were finished, I headed to the Maine cost to Eli's parents house. Their upstairs had been turned into a food prep room. Eli, Sage, and Steve were all busy over the week end so I took on food pack alone. Eli created our food system and gave me a detailed list of all the ingredients and meals. Sage finished up the details and did the final food shopping. When I arrived to the food room, everything was very organized and easy to find. "Eh food pack will be easy" I thought to myself. I got to work making food bag labels and creating an organization system. Being organized and systematic is probably one of the keys to a successful food pack, especially a big one. I organized a grid on the floor to separate food by breakfast, lunch, supper, and snacks. That was one axis, the other axis separated the food by barrel. Our food is organized so that the first 10 days is packed in a dry bag. The barrels are packed in layers, the top layer for the second 10 days, the third for the 3rd 10 days, and the bottom layer for the last section of the trip. All the barrels contain a combination of breakfast, lunch, supper, and snacks- that way, if we forget a barrel on a portage or lose it down a river we wont lose all our delicious oatmeal or chocolate bars. Food packing took hours. Meticulously weighing everything and then placing it on the grid. So far, I'm pretty happy with the performance of the food bags. The seams are sewn tight enough that flour doesn't dust out the sides! Working through the lens of a no single use plastic initiative has opened our eyes to just how difficult it is avoid plastic waste. We order a lot of our food in bulk, while this reduces waste and cost, food still comes packaged in plastic bags. Small pallets as still wrapped in plastic, We also order trip gear online and some of those items shipped in plastic bags. Some boxes even contained has air filled plastic bags as packaging material, not to mention the dreaded Styrofoam. On Future trips I'll reduce this by trying to purchase more food items and gear locally. Much of our food was from the Outward Bound 'roadkill' bin. Roadkill is food that went out on a course with participants, was left over, and is still in excellent condition, but for O.B. can't send it back into the field. Many of our grains, pastas, flour, cornbread mix, powered milk and a few other items we from this bin. Those items were still in their original plastic food bags. We repackaged these into our sewn food bags. Those plastic bags are added in to our plastic waste total, even though it isn't new plastic waste. Over all our food pack added 13.2oz to Eli's 9oz of plastic waste from food dehydrating, totaling 22.2oz. We inevitably missed a few things, but our push to buy consciously and use or own food bags greatly reduced what this could have been. Remember- we're not bringing back plastic waste! We will return with 75ish candy bar and energy bar wrappers. We ran out of time to make all of our own bars. Besides plastic, we had one paper grocery bag full of cardboard for recycling (not including a few shipping boxes), and several gallon containers from peanuts, nuts, potatoes, prunes, and cheese powdered. Not zero waste. We tried hard - and this processed open our eyes to just how difficult this is. Van packing  The next step in the prep process was packing everything in barrels and bags! We have checklists months in the making and most things were checked three times. Our food barrel packing session showed that we only missed one item (mung beans, impressive right?). It did enlighten us that our original plan of fitting all our food into 4 barrels was a distant dream. We had to add in an old 110L seal-line dry bag. Our barrels are full to the brim! We filled 43 containers from sQuishloc with varies wet ingredients and spices, like maple syrup, olive oil, jelly, lemon juice, molasses, honey, salt, cumin, garlic etc. We double checked all of our gear item by item. We packed repair kits for sewing, patching dry bags, fixing and patching boats, repairing bug mesh, and patching dry suits. We triple checked our first aid kit. We debated about if we really needed to bring a wooded spoon. We set up our tents and tarps and counted tent stakes. In the end all of our gear fit into one granite gear food bag and Duluth pack. Next we sorted through our own gear. Between the porch and backyard at Steve's house common questions were, "How many pairs of socks are you bringing? Should I bring my wind-stopper fleece or my cozy comfy fleece?" "Shit, where are my neoprene socks?" Final decisions were made and clothes, and sleeping bags are tucked away tight in our dry bags. We will make a last minute gear store stop in Burlington on our drive north- never found those neoprene socks! Last step- the final check and loading the van! And, with all of that- Beth and Steve are heading north! They will meet Eli and Sage in La Grande, Quebec on July 1st. The team flies to Umiujaq on July 3rd. We may check in on Facebook so like our page if you want to follow our progress. Thanks to all of you who have contributed in many different ways to make this trip happen. We'll be back at the end of August!

Like us on Facebook! Beth is back Stateside and the rest of us all had this past weekend available. Time to do some serious trip planning. There is no road to get to Umiujaq, so we'll have to fly. To make things more complicated, the airport that serves Umuijaq is an airstrip near the town of Radisson which is basically an outpost for Hydro-Quebec. To get there, you have to drive for 366 miles along a road with no development of any kind (save one service station staffed for 24 hrs/day at the half-way mark). It is known as the James Bay Road. To further complicate matters, we'll be bringing much more than a carry-on and a couple of checked bags (our gear estimate is 900 pounds, including boats and food) and the planes Air Inuit uses have limited cargo capacity. How, then, do we get our stuff up there? Did I mention we don't have a fat budget? That was one of the hurdles we approached (and almost jumped over) this past weekend. Another big item we discussed is what it would look like if something goes wrong - from minor to major. Nobody wants accidents to happen, but they do. It is why we have things like Ambulances, Fire Departments, and Hospitals. Trouble is, those human creations are stretched thin to non-existent when you get to the frontiers of civilization. We will be traveling beyond that frontier and into the wilderness. Without getting too bogged down into the definition of wilderness, or the ethical implications of the same, it is fair to say that the sheer vastness of the terrain in the interior of the Ungava peninsula qualifies it as a true wilderness. After we leave Umiujaq until we paddle into Kangirsuk about 40 days later we expect to see nobody. Who, then, will help us if something goes wrong? In the information (or should I say data?) age, you can push a button from anywhere in the world and tell the world that you need help. That technology is readily available, and certainly does lessen the risk margin of wilderness travel. But who is going to help you? With helicopters, float planes, military and civilian rescue teams, somebody will probably come eventually. But the cost of rescue can be enormous. Enter insurance. We don't plan to use it and we'll do everything we can to not do so, but you never know... So we've had some of those difficult, but important, conversations. On a happier note, we had some great gear planning and budgeting discussions about how to avoid single-use plastic. We're all committed to that plan and look forward to doing some serious field testing. We are assembling our gear, have now bought two pack-canoes, have a plan for how to pack our food and keep it dry with no single-use plastic, and we enjoyed the sunshine of a spring-weekend here in Vermont. We paddled the Mad River, made some yummy food with lots of veggies and some local meat, and cuddled with a cat. We have a master-plan for the next few months, with benchmarks and dates due for certain planning items. Beth, Eli and Sage will all be at Outward Bound and focusing their energy there for much of the next two months. I'll be preparing for a big party for Marisa's Masters' Graduation. The next moment we will all be together will be the beginning of June for All-Staff training at HIOBS. We will be able to get all the trip prep done, but it will be tight! Wish us luck, and if you want to help us get up there, donate below! Steve Somehow I lucked out and became a 27 year-old guy with strong organizational skills. Don’t worry, though, it doesn’t apply to all aspects of my life. I couldn’t tell you where to find my own wallet right now but could pull up a document that tracks every single penny of our food budget. So far, that is 35,747 pennies. I know where they all went, so I feel like that is pretty good. To wrap up my two weeks of full-time food prep, I estimated the cost of all our remaining food, made a shopping list with specific amounts, and estimated how many food bags we will need to pack all forty days worth of food (200 was the somewhat educated guess). All we have left to do this spring is buy dry ingredients and pack food bags. It will probably take a few days, though. The only exception is that we still need to dehydrate the fatty foods (jerky and eggs) in the spring, since they won’t last as long. It feels like I’ve done a lot, but all I have to show for it are a few (9 to be precise) pounds of vegetables and about 6 dozen glass jars filled with dehydrated food, all labeled with their weight and contents. Here are a few updates on the constraints I mentioned in my last post: -Minimizing or eliminating the use of one-time use plastics: Our original goal was to create no landfill waste. After a winter of food prep, I was left with 9 oz of landfill trash. When squished down, it was pretty close to the size of a softball. This trash included stickers from fruits and vegetables, a couple pieces of plastic wrap I experimented with early-on in the dehydrating process, plastic bags food had come in, and 5 pieces of parchment paper. All other waste ended up in my town’s single-stream recycling program (plastic and glass jars, boxes, cans, etc.), in my parent’s compost pile (lots of banana peels, pepper stems, and onion peels), or in my belly (kale stems, for example). To be honest, some of this waste was produced simply because even though I’ve been super organized with this whole food pack, I can still be very spacy. On three separate occasions, I simply got distracted by an awesome deal and forgot to seek out foods that didn’t come in plastic. I discovered that parchment paper can be used over and over in a dehydrator. That was an accidental and awesome discovery. I used the same 5 sheets of parchment paper for at least 7 rounds of dehydrating. They ended up in the trash after I tried to dehydrate cheese on them (don’t recommend it). The largest portion of landfill trash was intentional and conscious. I have discovered that it is really hard to buy some ingredients in anything but a plastic bag. The simple explanation is that a sealed plastic bag preserves food well. Nuts are a great example of this. Even when you find nuts in the bulk food section of a grocery store, those nuts were originally in a plastic bag. Produce is also transported in waxed cardboard boxes. The wax coating shifts these containers from the recyclable pile to the landfill category. When I started to put all these pieces together, I began to be more liberal with purchasing foods that came in plastic. My thought behind this was that I wanted a landfill waste number that accurately reflected how much trash had been produced during this food pack and didn’t just ignore the plastic I never saw because it was removed before I purchased a product. -Budget: As far as my double-checked estimations and triple-checked calculations are correct, we are right on budget, perhaps even a little under. -Weight: It seems a little mind-boggling to me right now, but we have 9 pounds of vegetables that are supposed to last us 40 days. It seems like nothing. But when you consider that it was over 100 pounds to start with, it doesn’t seem so bad. -Space: I have drawn complicated diagrams that so far I have not been able to explain to any of my expedition partners. The complicated packing strategy minimizes the amount of food bags we need, decreases the amount we have to dig through the barrels, and maximizes our safety if we lose a barrel. The goal is to fit everything into our four 60L food barrels. We will be baking every day, which decreases our food volume drastically. If you don’t understand why this is true, measure out 1 lb of flour (our 1-day ration) and compare its size to about 8 servings of your favorite cracker. -A complex palette: So far, almost everything I’ve made has tasted good to my front-country taste buds. I think the exceptions to this are a couple of bean accidents. One batch had waaaay too much cilantro and another had waaaay too much hot pepper. Whoops. They’re both going in the field with us. My mom recently told me a story about how her Hood River expedition team unanimously decided to throw all of their hummus powder into the wind when it made everybody’s farts unbearable. I hope we don’t have to do that. I quadruple rinsed all the beans. I hope that was enough. For the most part, I would consider the winter’s food prep a success. There were a few interesting learning experiences, though. Here are some of the highlights: -Most of the fruit leather turned into fruit crisp. I guess the perk is that it will probably last longer, since it has a lower moisture content. -Dehydrated cheese is absolutely not worth it in my unprofessional opinion. If you are going to try this, do yourself a favor and put your grated low fat-content cheese on a mesh rack and be prepared to clean up cheese grease out of the bottom of your dehydrator. -If you’re going to buy a dehydrator, get one with a timer. It makes a world of difference. -Poblanos and chipotle peppers are two very different things. Read the labels before you just dump a couple cans of chipotles in your shopping cart and later into your beans thinking they are poblanos. They aren’t. Sage and I have moved out of our food prep mansion and are on our way to North Carolina to instruct two different semesters, 50 and 35 days respectively. Beth arrived in Brazil yesterday to instruct a semester course down there. Steve will be cuddling with his cat during all of his free time for the rest of the winter. Actually, I don’t think he really has any free time this winter. So for now, trip prep is getting put on hold. Our prototyped food bags are going into the field with Beth, Sage, and I. We are keeping our fingers crossed, since we already bought the fabric. And thirty-five thousand, seven hundred and forty-seven pennies worth of food is being stored in my parent’s basement. Farewell for now. Check back in the spring for more updates. AuthorEli Walker, Food Guru 4 high school dorm rooms, 3 college dorm rooms, an over-sized windowless closet in Minnesota, the back of my Subaru Legacy, a Ford Transit Connect, 3 cabins at 2 different Outward Bound base camps, and a tent that could be found anywhere between northern Maine and Las Vegas depending on the season. What do these places have in common? These are the places I have lived over the last 13 years. Up until a couple months ago I had never paid rent, travelling seasonally with the birds to follow my dream job as an Outward Bound instructor. This past December, my fiance and I decided to try something a little different and settle down... for three months... in between our New Mexico climbing trip and our return to Outward Bound in the spring. Our short stint living in a heated house with plumbing and electricity has been nothing short of splendid. It has been wonderful to have something that we can call home but has also made preparing food for Canoe Ungava possible. We currently have an entire room in our house, half of our freezer, and a shelf in the fridge designated to Canoe Ungava food prep. The food room, as we have started to call it, is filled with ingredients purchased in bulk, two dehydrators, a small scale, a food processor and blender, and about four dozen mason jars labeled with their contents and weight. It doesn't sound like much, but I don't think this project would have been possible without all the space. We certainly could not have done this in the back of our van! Last week I quit my temporary warehouse job in order to put in full-time hours preparing, drying, and packaging food. My new-found occupation, although unpaid, is exponentially more enjoyable. I love the problem-solving, the flexible hours, and the way the house smells after making three batches of granola. For the past week, my typical day has started by checking on the trays around 6:30am, often before I even go pee, and usually ends when I put the last batch of trays into the dehydrators right before I go to bed at 9:00pm. I have 10 more days of full-time food prep before Sage and I move out of our house and go back into instructor lives and Beth begins instructing a semester course in Brazil. In 10 days, 99% of all trip planning will be put on hold until May. Luckily, I am nearing the end of what originally felt like an impossibly long list of items to prepare. My goal is to finish the bulk of the dehydrating so that all we have to do in the spring is purchase and pack the remaining foods. Luckily I love problem-solving, because our food packout is not exactly straight forward. What is the goal? Make as much delicious food as possible that is low cost, high calorie, compact, and light weight. The constraints? -Minimizing or eliminating the use of one-time use plastics: Hm. Easier said than done. -Budget: $8 per person per day for food -Weight: We will have to carry ALL of it on each of our portages. We will be starting with 40 days of food (a little over 300 lbs), and portaging begins on day 1 of our expedition. -Space: We have four 60-litre barrels that our food needs to fit into to protect it from black bears and water, and the barrels need to fit into our 17' boats along with the rest of our gear -A complex palette: Four mouths, each of which has eaten countless meals in the field, which essentially just means that each of us has some things that we simply won't eat: for example, instant oatmeal. Check back next week for updates and accomplishments (and maybe a few failures) on my two weeks of full-time food prep. A typical morning in the food room. AuthorEli Walker, Food Guru That's what I thought. Easy. One year into research and product testing; not so easy.

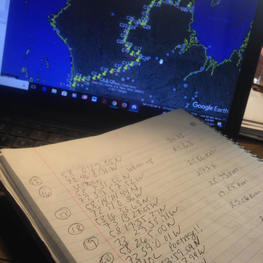

It's hard to find a product that is not only reusable, but also durable. I experimented with several brands of reusable ziplock bags. Over all, I wasn't impressed. After two months on rugged expeditions, in Brazil last spring, the plastic began to separate from the zipper, the seal wasn't as sound, and there were a few holes. They were way more durable than a regular ziplock bag, though I expect their life span wouldn't last through too many expeditions. Lastly, the higher price tag doesn't make them appealing for a long expedition in need of 150 bags. Next option. I'll just make my own. Easy right? Ha, no. I'd like to offer a big thanks to all the moms who have worked to make reusable food safe snack bags. Their research became my jumping off point. First- What is the purpose of a food bag on expedition? It keeps food dry. It's not breathable- it doesn't allow dried food to absorb moisture. It needs to be durable. Weight matters. Second- The material has to be food safe. This has been challenging to address. This is where those snack bag making moms were a big help. Third- Construction. Sewing is the most practical. However the seams of a waterproof fabric quickly become not waterproof when sewn. Sealing them opens the door to a huge amount of research- food safe adhesives or seam tape that adheres to said fabric. This question led me down a rabbit hole into the world of industrial food packing adhesive manufacturers. Then I began to ask is seam sealing worth it? Step Four- Testing the first prototype. I'm not 100% satisfied with the product. The seams aren't sealed, the fabric is different than I expected. They are food safe, machine washable, the fabric is waterproof (up to 300 washes), and they're not too heavy. Fifth- Keep researching! I'm still investigating more materials and construction methods. Big Adventure We all have spent years of our lives taking others on adventures. This adventure is for us. Rejuvenation. We want the unknown, new places, more days, remote wilderness adventure. No Single-Use Plastic Too many backcountry expeditions end with piles of plastic bags thrown in the trash. We want to eliminate that. We want to design, create, and test a waterproof reusable and reliable food storage bag. Traverse the Ungava Peninsula We'll start with our toes in Hudson Bay and end with them in Ungava Bay. Human Powered. Yes, we'll portage from the airport to the ocean. And then, the ocean to the airport.  One of the best places to begin route planning? Google Earth. Each day's travel length can be measured. Each proposed campsite's Lat and Long measurements can be recorded. Waterfalls can be seen, images from other adventures can be viewed. Imagine entering this area even, 120 years ago. Inaccurate maps and no information. Or, with a hand drawn map, a hunch and large sacks of flour, sugar, and salt. I can't fathom adventuring like the first explorers. Over-planning and information gathering can easily hinder the expedition prep process. Can't we just go already? If you're into adventure stories, check out Great Heart: The History of a Labrador Adventure. A 1903 ill-fated expedition into the unmapped Labrador Wilderness was a race for fame for Leonidas Hubbard that he would not survive. That gave way to a 1905 expedition crafted and completed by his wife, Mina Hubbard and her fantastic Cree Guide, George Elson. This expedition made headlines around the world. These days I can explore waterfalls, rivers and mountain tops around the world, in moments immediately after the thought occurs. Today I stood on the east face of Annapurna. Holy moly is that mountain steep. The world of adventure sure has changed in the last 120 years. I can take a flying tour of our expedition route at an altitude of 164 feet. Let's face it, it is hard, impractical, and almost impossible to escape from using plastic. My PakCanoe has plastic parts, my favorite fleeces contain plastic fibers, most of my back country travel gear contains some kind of plastic synthetic material. I'm not ready to trade my cozy sleeping bag for an elk skin or my lightweight rain pants for a heavy waxed canvas pair. I am ready to be conscious of my one time use plastic consumption; the things I buy that only get use once and tossed.

Food packing for expedition travel often looks like taking food out of its original grocery store packaging (usually plastic) and putting in an easy to open and close plastic bag. Things get packed by meal, organized so that each meal and its ingredients are bagged individually. In the backcountry this means that food stays dry and organized, but each meal produces several plastic bags that get thrown away at the trip's end. I am tired of bringing groups back from expeditions and throwing away trash bags full of plastic bags. As innovative, conscientious, adventurers, we can do better. The outdoor industry can do better. Leave no trace ethics should extend beyond picking up food waste at our campsites. It should raise the question: What is the overall impact of my expedition? The Task. How do we pack 40 days of food with no one time use plastic? How do we purchase food when trying to minimize waste? Stay Tuned for Canoe Ungava food packing updates. |

AuthorsBeth Jackson Archives

September 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed